En el sueño del hombre que soñaba, el soñado se despertó…

Jorge Luis Borges 1

Un artista de Buenos Aires

En 1993, con tan sólo veinte años, Leandro Erlich desarrolla un proyecto singular: la posibilidad de construir una réplica del Obelisco de Buenos Aires – uno de los monumentos más importantes de la ciudad, de 68 metros de altura – en el barrio marginal de La Boca. La empresa supone una reconfiguración de la vida urbana de la capital argentina, para la cual dicho monumento es un referente de ubicación geográfica, escenario de festejos y manifestaciones sociales, y marca de identidad.

En esta obra jamás realizada ya se percibe el interés del artista por los desplazamientos y las operaciones que trastocan la habitualidad de los espacios cotidianos. Pero lo más notable en ella es su nivel de ambición, poco común en un país donde los jóvenes creadores deben adecuarse a los medios tradicionales ante la falta de recursos para la producción de otros tipos de trabajos. Erlich asume un proyecto que evidentemente lo supera, pero que de alguna manera también lo entrena para abordar aquello que se muestra, a primera vista, como imposible. Su herramienta más poderosa en estos años no es técnica, ni siquiera lo es su aguda imaginación, sino que es, más bien, esa actitud intrépida que lo anima a internarse en terrenos desafiantes y complejos.

Su obra actual conserva el germen de ese reto primero. Sus instalaciones de espacios simples, banales y cotidianos no buscan llamar la atención sobre éstos, sino que son dispositivos destinados a cuestionar las formas en que aprehendemos la realidad a partir de la precaria información provista por nuestros sentidos. Sus reproducciones de espejos, ventanas y espacios laberínticos no se agotan en la constatación del carácter equívoco con que se presentan a nuestros ojos, sino que se orientan a sembrar la semilla de la duda sobre toda aproximación al mundo que conocemos, a través de los datos suministrados por nuestra percepción. En este sentido, su programa es tan ambicioso como el intento aparentemente ingenuo de replicar el monumento más importante de la ciudad con tan sólo veinte años. O lo es aún más. Porque se dirige hacia facultades modeladas fisiológica e históricamente pero que atraviesan geografías y culturas, incluso en piezas con referencias muy locales como Turismo (2000) y Window and Ladder (2008).

Los estudios sobre la obra de Leandro Erlich resaltan su evidente relación con el universo poético de Jorge Luis Borges. Su afición por los laberintos, las paradojas y los espejos no deja ninguna duda al respecto. El propio artista ha declarado en numerosas oportunidades su admiración por el escritor, que en la Argentina es un referente cultural insoslayable. Sin embargo, existe otro aspecto que los une de manera íntima: la mirada distanciada, analítica e inteligente que ambos proyectan más allá de su entorno inmediato, y el permiso que se conceden para realizar sus aportes a la cultura universal desde una de las ciudades más alejadas de los centros culturales del mundo.

Se podría argumentar que en un mundo globalizado las distancias son relativas y que ya no hay centros privilegiados de producción de cultura, pero una rápida observación a la actividad cultural del planeta desmiente de inmediato esta afirmación demasiado optimista y posmoderna. En todo caso, sería mejor acudir a una explicación más plausible y reiterada: que la Argentina es un país conformado en su mayoría por descendientes de inmigrantes europeos que miran con insistencia y admiración hacia el locus de sus orígenes. Pero esto tampoco es suficiente, ya que existen miles de artistas y escritores de este país que no se sienten llamados a trascender las fronteras nacionales.

Leandro Erlich pertenece a una generación de artistas argentinos que se interesan por hacer oír su voz en la escena internacional, convencidos de poder realizar una aportación significativa al campo dialógico y reflexivo de la creación contemporánea. Como Tomás Saraceno (un artista de su misma edad), y más recientemente, Adrián Villar Rojas, reniega de los temas locales, y del tipo de producción low-cost y de materiales precarios que se asocia con los autores de América Latina. En contrapartida, sus trabajos emplean recursos sofisticados y los mismos niveles de realización de sus colegas del mundo. El uso frecuente de materiales y técnicas del ámbito de la construcción edilicia lo ayuda también a evitar los tonos locales, en la medida en que la arquitectura posee hoy un grado de estandarización tan alto que evade cualquier identificación con un contexto específico.

La relación entre Leandro Erlich y Tomás Saraceno es particularmente interesante. Ambos se orientan hacia el cuestionamiento de la realidad apelando a configuraciones y procedimientos que la relativizan; el primero, a través de diferentes formas de artificio; el segundo, mediante el recurso a una discursividad de ribetes utópicos. En su capacidad para trascender las imposiciones del mundo tal como lo conocemos, estos dos artistas encarnan un tipo de pensamiento que aborda críticamente determinados aspectos del mundo contemporáneo, recurriendo al ingenio y la poesía, la promoción de universos alternativos y el diálogo abierto con el público.

Este inconformismo es parte de una aproximación a la realidad que pregunta de manera constante por la naturaleza, el funcionamiento y los límites de las cosas. Al respecto, es significativa la situación que da origen a la obra Ascensor (1995), con la que Erlich participa del prestigioso Premio Braque de Buenos Aires. Según cuenta el artista, la idea que la generó fue proporcionada por las propias bases del concurso, que establecían que las dimensiones máximas admitidas para objetos eran de 80 x 80 x 180 cm. Tras preguntar el motivo, se enteró que eran las medidas del ascensor de la institución donde se desarrollaba el certamen, el medio que se utilizaría para introducir las piezas artísticas al lugar.

La obra reproduce la cabina de un ascensor con su interior y exterior invertidos: del lado de afuera se encuentran la botonera y la decoración típica de uno de estos dispositivos de transporte; en el interior, un juego de espejos produce un cableado virtual infinito. La anécdota es relevante en más de un sentido. No sólo por el ingenio con el que el joven artista se burla de las dimensiones permitidas, sino fundamentalmente porque en su interior el ascensor excede tal limitación a través del juego especular. En esta transgresión de los límites, Erlich cuestiona no sólo las reglas impuestas a la producción artística, sino también a las instituciones que las crean con arbitrariedad.

Casi de inmediato, su interés se desplaza hacia los juegos ópticos, las falsas perspectivas, y en particular, hacia la activación del lugar del espectador. Las instalaciones Neighbors (1996) y The View (1997-2005) construyen un punto de vista que ubica a éste último como voyeur. La primera propone observar el pasillo de un edificio virtual desde la mirilla de una puerta; la segunda, invita a espiar, a través de una persiana, las actividades que los habitantes de un edificio realizan con las ventanas abiertas.

A diferencia de lo que sucederá después, aquí los espectadores no pueden ingresar a las obras; sólo miran desde el espacio que les ha sido asignado en el exterior de éstas. Esto permite que, mientras esperan su turno, asistan al acto de observación de los demás. Se establece de esta manera una situación especular mediante la cual el futuro mirón toma conciencia del acto que está por llevar a cabo. En las próximas instalaciones será un espejo, por lo general, el encargado de enfrentar al público con sus propias acciones.

En The View aparece por primera vez un componente narrativo fuerte, que será poco frecuente en el trabajo posterior de Erlich, pero que se hace indispensable para sostener la mirada durante un tiempo prudencial. Con la reaparición del video en sus obras recientes, la narrativa vuelve a ocupar un lugar destacado, pero ésta se basa ahora en una suerte de temporalidad cíclica y repetitiva, en la cual se va diluyendo el interés por la progresión de las imágenes (Subway, 2009; Elevator Pitch, 2011; entre otras).

De hecho, la utilización de la imagen electrónica en las obras de Leandro Erlich es menos narrativa que espacial. En consonancia con el resto de su producción, el video introduce un ámbito virtual, un espacio-otro trasladado a la galería, generalmente mediante un marco o decorado que lo adapta a las exigencias de una escena. Las secuencias audiovisuales – que muchas veces no poseen sonido – se ajustan a los parámetros de la verosimilitud cinematográfica en tanto ella es la responsable de lo que consideramos realista. Pero no hay un uso argumental del medio. En todo caso, es el marco que cobija al video el que aporta los elementos necesarios para que éste adquiera carácter narrativo (en su mayoría, los videos simulan estar del otro lado de una ventana, en un espacio adyacente).

La abominación de los espejos

Con la producción de El living (1998), Leandro Erlich adquiere el impulso definitivo que lo ubica en el camino hacia la madurez estética y conceptual. Aquí la arquitectura cobra protagonismo y el espectador pasa a ser un agente exploratorio que, engañado en su aproximación primera, debe reajustar su lectura hacia la comprensión de los mecanismos que gobiernan su mirada.

La instalación muestra un living cuya pared presenta dos aberturas: una de ellas es un espejo que refleja la habitación mientras la otra es una ventana que se abre hacia un cuarto exactamente igual al primero pero invertido, a la manera de un espejo en el cual no aparece la imagen del espectador. El descubrimiento de este espejo que no refleja es estremecedor y en algún punto siniestro. En el cuento Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, Jorge Luis Borges ponía en boca de su amigo Adolfo Bioy Casares una frase igualmente inquietante: “Los espejos y la cópula son abominables, porque multiplican el número de los hombres”.2 ¿A qué se debe el carácter abominable de la reproducción?

En la literatura, las leyendas y los mitos, los espejos aparecen muchas veces ligados a referentes mortuorios. La ausencia de reflejo recuerda de inmediato a la historia del Conde Drácula, quien pone en evidencia de esta manera su falta de vida y realidad. El mito de Narciso deposita en la duplicación especular la causa de la muerte de su protagonista, enamorado de su propia imagen hasta abismarse en ella. En la teoría lacaniana, la fase del espejo constituye una instancia clave en la construcción de la subjetividad y en la autoaprehensión del individuo como ser imaginariamente completo; la incapacidad de superar esta etapa en un momento clave de la vida puede llevar a diferentes formas de anulación o autodestrucción.

Sin embargo, la inquietud que produce esta obra no se reduce al descubrimiento del falso espejo. Existe, además, una tensión entre realidad y representación – desplegada a través de un magnífico trompe l’oeil – en la que se postula, de alguna manera, la posible falsedad del mundo que habitamos. “Más que la preocupación por la esencia del modelo y su reconstrucción puntual – sostiene Severo Sarduy – [el trompe l’oeil] parece empecinado en la producción de su efecto. De allí la intensidad de su subversión – captar la superficie, la piel, lo envolvente, sin pasar por lo central y fundador, la Idea – y la agresividad que suscita en los reivindicadores de esencialidades la extrañeza de su teatralidad que funciona como en un vacío”.3 La vacuidad de ese universo representado como espejo del nuestro, no hace sino señalar la latente vacuidad del que le sirve como modelo.

“Esta eficacia, la de hacer visible lo inexistente – continúa Sarduy –, no parte, sin embargo, de la afirmación o apoteosis de una personalidad, de un estilo, sino al contrario, de su disimulación máxima, de su anulación: mientras más anónimo en su ejecución, mientras menos se exhiba o denuncie el trazo, más eficaz es el trompe l’oeil”.4 En el límite del engaño, la obra no delata la mano de ningún autor y deja al espectador solo frente a la conmoción de su universo perceptivo. El descubrimiento de la trampa produce un efecto de extrañamiento, en el sentido brechtiano del término. La pieza muestra los mecanismos mediante los cuales produce la significación sólo para que, en el momento crítico, el espectador reflexione sobre la precariedad de sus interpretaciones a partir de los datos que provee la experiencia desnuda.

Así, la instalación se proyecta más allá de la mera superficie de lo reproducido para internarnos en la examinación consciente de nuestro entorno. Como sucede con las fotografías de Jeff Wall, la puesta en escena nos reconduce a considerar críticamente los vínculos entre realidad y representación, a agudizar nuestra percepción de lo cotidiano, a indagar en los cimientos culturales de la mirada, y a sopesar los efectos de la cosmética espectacular habituales en nuestro entorno contemporáneo.

Como sostiene Jacques Lacan: “el mundo es onmivoyeur, pero no es exhibicionista: no provoca nuestra mirada. Cuando comienza a provocarla, entonces también empieza la sensación de extrañeza”.5 La sala invertida en El Living se descubre dotada de una mirada independiente de la posición del espectador, ajena y desnaturalizada. Esa mirada lo preexiste, lo transforma en actor del “espectáculo del mundo”, al decir de Maurice Merlau-Ponty. Esta conciencia de convivir con otra mirada es, quizás, uno de los aspectos más perturbadores de la obra.

La fascinación por lo especular se aprecia en numerosas obras de Leandro Erlich, aunque de maneras muy diversas. En Cadres Dorés (2007), aparece materializada en dos pequeñas instalaciones enfrentadas que reproducen el efecto-infinito de la oposición de dos espejos. En Sidewalk (2007), los edificios de una gran ciudad se hacen presentes en la galería a través de sus reflejos en un charco de agua. The Ballet Studio (2002), introduce un elemento más curioso: aquí, la reproducción de dos espacios iguales pero invertidos se completa con una coreografía estrictamente sincronizada, interpretada por dos bailarinas muy parecidas y vestidas de igual manera. El “reflejo” ahora tiene vida propia ¿Pero cuál de los dos espacios debería ser considerado como tal?

En Changing Rooms (2008), el espectador es invitado a atravesar espejos hasta perderse en un espacio confuso y laberíntico. La multiplicación de los diminutos vestidores que se continúan en diferentes direcciones genera una sensación inquietante y claustrofóbica. La repetición da paso al virtuosismo escenográfico que empata los objetos de la realidad de una manera tan precisa que cuesta aceptar el engaño, incluso luego de haber traspasado los marcos dorados que deberían contener espejos en más de una oportunidad. Adivinar el funcionamiento de la pieza es menos importante que admitir su funcionamiento magistral.

Sumergirse en lo cotidiano

La pileta (1999) constituye otro hito en la carrera de Leandro Erlich. Mientras en El living el espectador es introducido de manera gradual a la irrealidad del simulacro, aquí es lanzado de lleno en ella. Ingresar literalmente al interior de una piscina es una experiencia que puede provocar sensaciones equívocas, pero todas ellas ajenas a nuestro vínculo con lo habitual. El color celeste de las paredes, los reflejos ondulantes, la luz que nos llega atravesando el espejo de agua, construyen una experiencia excepcional e inmersiva que se adelanta a su posterior captación por el intelecto.

Reflexionando sobre el ensayo The Sublime is Now, de Barnett Newman, el filósofo Jean-Francois Lyotard se pregunta: ¿Cómo se puede pensar en lo sublime como “aquí y ahora”? ¿Acaso lo sublime no es algo más allá de la experiencia habitual? Su conclusión sostiene que la experiencia del aquí y ahora, que debiera ser una de las más cotidianas, se ha vuelto inusual.6 En la obra de Leandro Erlich, la conciencia del aquí y ahora precede a su intelectualización ulterior. Aun cuando después se descubra el artificio, existe una primera afirmación del espectador en sus propios datos sensoriales que induce esa “suspensión del descreimiento” que Borges exigía para la experiencia estética.

El shock que produce inicialmente la pieza merece algún comentario. En la década de 1930, Walter Benjamin lo saludó como una de las aportaciones más originales del cine a la recepción artística, y ubicó sus antecedentes en las prácticas vanguardistas del dadaísmo.7 Hoy ese efecto forma parte del repertorio de los medios de comunicación que recurren al sensacionalismo como método de atracción de las masas. Sin embargo, la perplejidad que provoca La pileta posee un sentido diferente. Pues si los dadaístas acudieron al shock para conmover la cotidianidad y los mass-media lo usan para alejarnos de ella, los artistas contemporáneos apelan a él para reafirmar la experiencia cotidiana, para exaltar el aquí y ahora de su aparición.

Según Fredric Jameson, la desrrealización presente en una buena parte del arte contemporáneo conlleva una aguda reflexión sobre la realidad.8 Pero, ¿a qué realidad refiere una obra como La pileta? En unas entrevistas radiales, Claude Lévy-Strauss notó cómo el impresionismo se orientó hacia los paisajes en el momento en que éstos estaban desapareciendo como espacio vital para el habitante de las ciudades del siglo diecinueve.9 Quizás se podría afirmar que en La pileta, la vivencia del ocio, del disfrute de los sentidos, del placer de la recreación, plasma una experiencia cada vez más distante para el habitante de las deterioradas metrópolis contemporáneas.

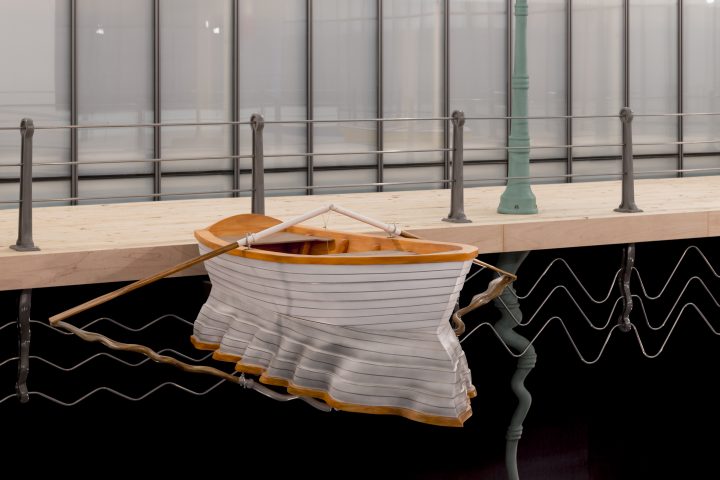

Desde el punto de vista formal, la pileta juega con un conjunto de inversiones: adentro/ afuera, arriba/abajo, interior/exterior, etc., que reaparecen en obras como La torre (2007), The Shaft (2011), Staircase (2005), y en varias instalaciones basadas en videos, como Le Regard (2011), Subway (2009), o Window Captive Reflection (2013). También introduce el interés del artista por las perspectivas bajas y elevadas, que puede apreciarse en Eau Molle (2003), Sidewalk (2007), Window and Ladder (2008), Double Skylight (2009) y Le Monte-Meubles (2012). Finalmente, aparece aquí por primera vez el motivo recurrente del agua, que anima piezas como Rain (1999) o Eau Molle (2003), entre otras.

Creatividad colectiva

Turismo (2000) es una obra atípica en el trabajo de Erlich, pero con ella se inicia una serie de proyectos que otorgan un lugar protagónico al espectador. Es atípica porque se trata de un trabajo en colaboración (con Judi Werthein), pero principalmente, porque los artistas son los encargados de organizar y hacer funcionar el dispositivo ficcional en el que se basa la pieza. En las sucesivas, Erlich estará por completo ausente, depositando en el público la responsabilidad de activarlas.

La obra reproduce un estudio fotográfico compuesto por un telón con un paisaje nevado, varios tipos de trineos y nieve artificial. Durante largas jornadas, una multitud de cubanos se apiñan frente a la instalación para obtener una fotografía polaroid que los muestra en un entorno invernal, armado al mejor estilo hollywoodense. Aquí la puesta en escena es evidente desde el principio. Pero, paradójicamente, el artificio desaparece al final: las fotografías nevadas parecen reales, o en todo caso, detentan la realidad prefabricada propia de cualquier estampa turística. La principal nota de realismo fue concebida por el propio público, que comenzó a acudir a la sesión fotográfica con ropa de abrigo, a pesar de las altas temperaturas del noviembre cubano.

Turismo activa una serie de interpretaciones inmediatas. En principio, introduce a sus protagonistas en una experiencia a la que pocos tienen acceso, no sólo porque en Cuba no nieva, sino más bien, porque la posibilidad del turismo suele estar vedada a sus habitantes. Incluso son pocos los que poseen fotografías, ya que no existe en la isla la manía fotográfica propia de nuestras sociedades capitalistas. Hay, por otra parte, una reflexión sobre la forma en que los medios modelan nuestra relación con el entorno. La fotografía, productora de sensaciones tan vívidas que llevaron a Walter Benjamin a afirmar que “la diferencia entre la técnica y la magia es, desde luego, una variable histórica”,10 existe hoy casi exclusivamente del lado de la técnica, como un formato de registro estandarizado. Poco queda de su magia inicial, a no ser para los cubanos que la transformaron, con su imaginación y sus sueños, en el reservorio de una situación vívida.

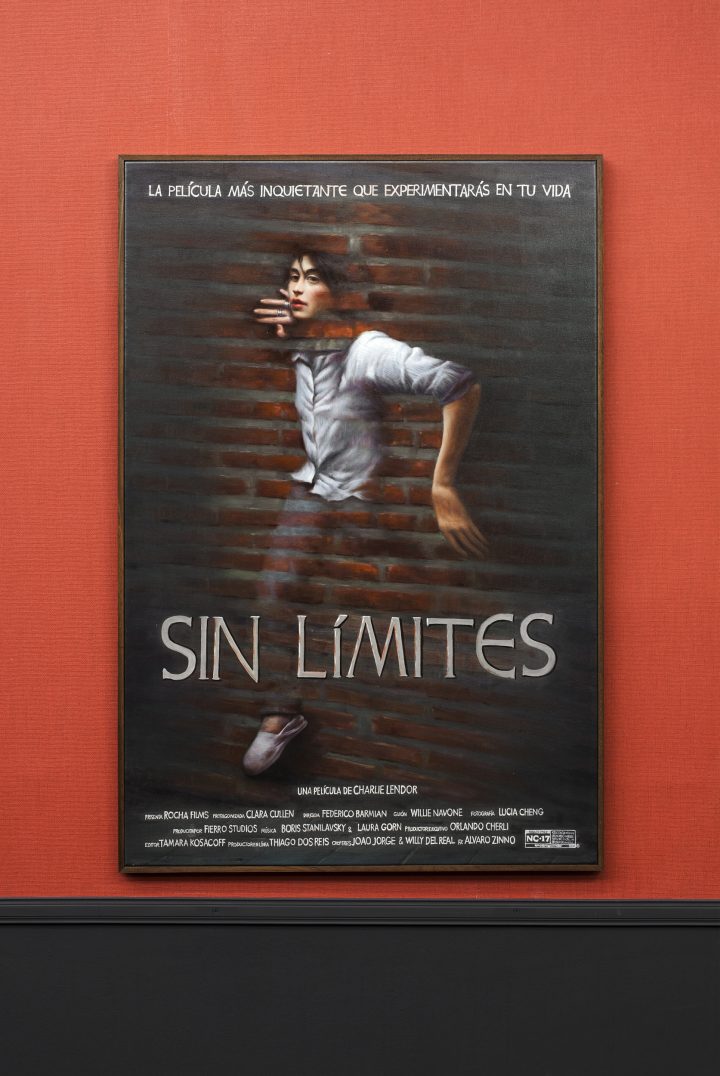

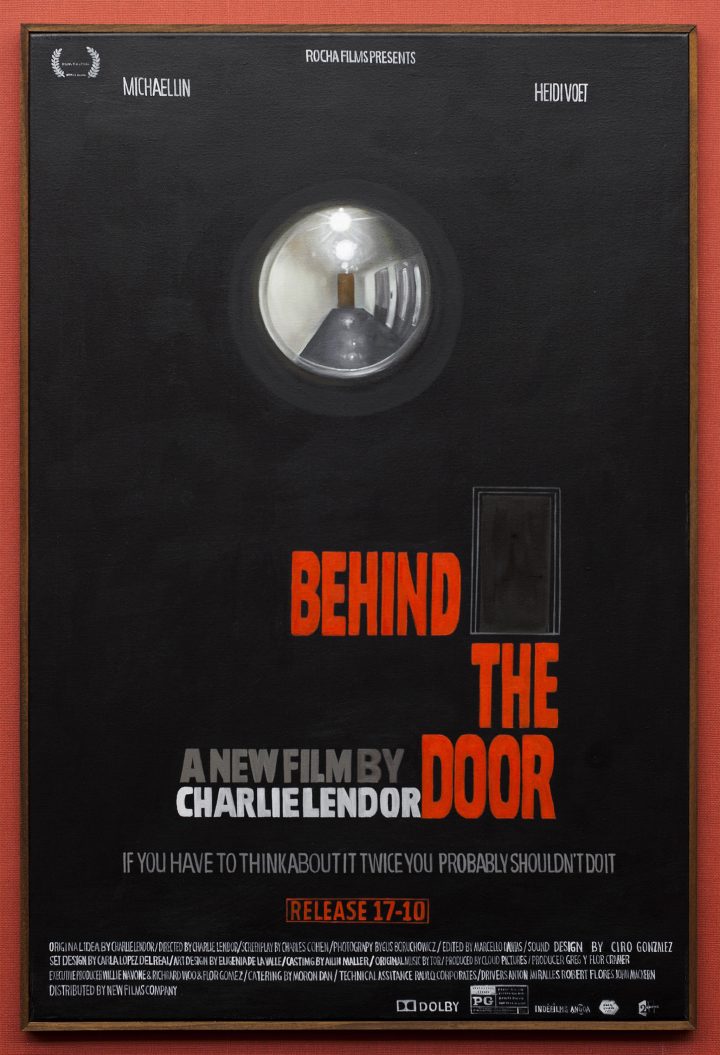

Otro caso destacado es el de las diferentes versiones de Bâtiment (2004-2013), realizadas en espacios públicos de París, Londres, Shanghái y Buenos Aires, entre otras locaciones. En ellas, la fachada de un edificio reproducida al nivel del piso pero reflejada en un enorme espejo que la erige a la mirada perpendicular, permite al público crear situaciones de alteración gravitacional. Como en Turismo, una fotografía tomada con el encuadre preciso oculta el artificio en forma tal que se hace difícil descubrirlo si no se ha estado presente en la producción del registro.

La creatividad de la gente que “usa” la instalación es tan grande que el artista se ha dedicado a recopilar las fotografías tomadas por los usuarios, transformando a algunas de ellas en obras autónomas. Las expresiones de los rostros, las posiciones estudiadas, la complicidad momentánea con los demás para no echar a perder el engaño, y la velocidad con la que se comprenden y adoptan los mecanismos ficcionales para utilizarlos en la construcción de imágenes verosímiles, ponen en evidencia la eficacia relacional de la instalación y su capacidad para despertar la imaginación del público.

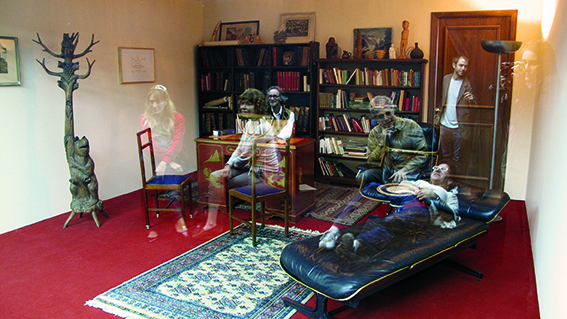

En una línea similar, aunque menos multitudinaria, Le Cabinet du Psychanalyste (2005), The Chairman’s Room (2012) y La Répétition (2014), animan también a la participación del público en forma creativa. Aquí, éste debe ocupar ciertos lugares que se corresponden con los espacios vacíos de una escenografía exhibida detrás de un vidrio reflejante. La posición correcta da vida a un escenario virtual poblado por los cuerpos fantasmagóricos de los participantes. Desde la serenidad de su ubicación, éstos pueden analizar el funcionamiento de los efectos ópticos, la importancia capital de la luz, las imprecisiones del acto de la percepción, las variaciones de los puntos de vista. De esta forma, se busca que su intervención sea, a la vez, lúdica y reflexiva.

Tipologías de la magia

Desafiar la gravedad, invertir los espacios, engañar al ojo, transformar al espectador en voyeur, forzar las perspectivas, manipular la duplicidad, instrumentar efectos especiales, incentivar la curiosidad, convertir al espectador en actor, activar escenarios banales, trastocar la temporalidad mundana, expandir espacios, abrir ventanas a otras realidades, reinterpretar lo cotidiano, suspender las definiciones de lo verdadero y lo falso, construir verosimilitud, provocar identificación, potenciar lo insólito. Estos son algunos de los recursos que Leandro Erlich ha desarrollado en su todavía relativamente corta carrera. A través de ellos, pone en entredicho la habitualidad del mundo en el que vivimos y de los automatismos en nuestra relación con él.

De esta forma, Erlich pone en escena su espíritu inconformista. No ya el de los jóvenes revolucionarios de los sesentas, sino quizás uno más modesto pero no menos efectivo, que se niega a aceptar la realidad tal como se ofrece configurada al hombre contemporáneo. En sus piezas los límites entre realidad y representación se confunden, no sólo para denunciar la construcción insidiosa de la realidad, sino además, para indicar las posibilidades reales de reactivar la experiencia a través de la representación. Sus obras causan extrañeza, asombro, desazón, reticencia, desconcierto, sospecha. Pero casi nunca indiferencia.

Notas:

1. Borges, Jorge Luis, “Las ruinas circulares” (1956), en Borges, Jorge Luis. Ficciones. Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1986.

2. Borges, Jorge Luis, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”, en Borges, Jorge Luis. Op.cit.

3. Sarduy, Severo. Ensayos generales sobre el barroco. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1987.

4. Ibídem.

5. Lacan, Jacques. El seminario 11: Los cuatro conceptos fundamentales del psicoanálisis (1964). Buenos Aires: Paidós, 1991.

6. Lyotard, Jean-Francois, “The Sublime and the Avant-Garde”, en Benjamin, Andrew (ed). The Lyotard Reader. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

7. Benjamin, Walter, “La obra de arte en la era de su reproductibilidad técnica” (1936), en Benjamin, Walter. Discursos interrumpidos I. Madrid: Taurus, 1974.

8. Jameson, Fredric. Ensayos sobre el posmodernismo. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Imago Mundi, 1991.

9. Lévy-Strauss, Claude. Arte, lengua, etnología. México; Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 1975.

10. Benjamin, Walter, “Pequeña historia de la fotografía”, en Benjamin, Walter. Op.cit.