Born in Buenos Aires, 1960. Lives and works in Brooklyn, USA.

He received a B.Sc. in Chemistry and Biochemistry from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Studied History of Photography and Photographic Aesthetics with Juan Travnik. She earned an MFA in Studio Arts from Hunter College (CUNY/City University of New York) in 2010 where she has also been teaching since 2009.

Grinblatt pursues a systematic program of exploration of the modes of perception enabled by the photographic image, in which she engages with the technical, artistic and social dimensions of the photographic device and emphasizes the “camera” apparatus as the bearer of a system of representation. In Buenos Aires, he had solo exhibitions at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires in 2001, the ICI in 1999, and the Rojas in 1995.He has participated in curated exhibitions at the Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid; MoMA PS1 and El Museo del Barrio in New York, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Philadelphia (USA); the Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels (Belgium); the Amos Anderson Art Museum (Helsinki, Finland); and the Museo de Arte Zapopan (Guadalajara, Mexico), Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (Buenos Aires, Argentina), among others.

His work is part of several public collections, including those of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Museum of Photography in Berlin, and the Museums of Modern Art in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro.

Individual exhibitions

2019

Usos de la fotografía IX / Mirando a Morandi. Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2017

Pasillos, Minus Space. Brooklyn, Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2016

Usos de la Fotografía VII / Fotos, Instalación site-specific. Buenos Aires, Argentina

Cielito lindo, Magil Library, Haverford College. Filadelfia, Pensilvania, Estados Unidos

Corridors/Pictures of nothing, Centro Cultural Pérez de la Riva. Madrid, España

2013

Cielito Lindo, Minus Space. Brooklyn, Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2010

Spazi (dis)abitati – Pasillos/Fotos de nada, Fondazione Teatro Lirico di Cagliari, Italia

2009

Usos de la fotografía-V/Dials/Cielito lindo, Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte. Buenos Aires, Argentina

2007

Cielito Lindo Fotología 5, Universidad Nacional, Centro Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. Bogotá, Colombia

Pasillos/Fotos de nada, Antta Gallery. Madrid, España

2006

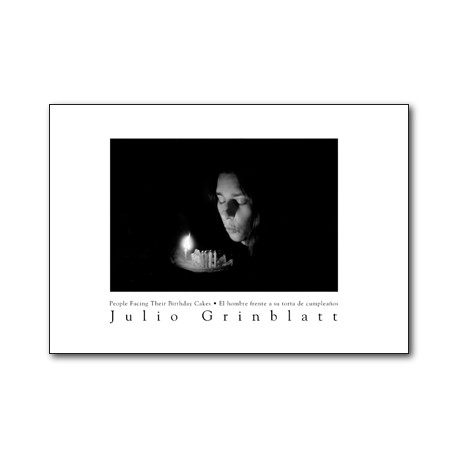

So Now Then/El hombre frente a su torta de cumpleaños, Hereford Photography Festival, Courtyard Center for the Arts. Hereford, Gran Bretaña

2005

Cielito lindo, Slought Foundation. Filadelfia, Pensilvania, Estados Unidos Pasillos/Cielito lindo, Baró Cruz Gallery. São Paulo, Brasil

Usos de la fotografía-II/El hombre frente a su torta de cumpleaños, LMI. Ciudad de México, México

The Gershman Y- The Open Lens Gallery. Filadelfia, Pensilvania, Estados Unidos

2003

Usos de la fotografía-I/Fotos de otros, Blue Sky Gallery. Portland, Oregon, Estados Unidos

Usos de la fotografía-I/Fotos de otros – Pasillos, Laura Marsiaj Arte Contemporânea. Rio de Janeiro, Brasil

Usos de la fotografía-II/El hombre frente a su torta de cumpleaños, Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte. Buenos Aires, Argentina

2002

Pasillos, Society for Contemporary Photography. Kansas City, Estados Unidos

2001

Usos de la fotografía-I/Fotos de otros – Pasillos Museo de Arte Moderno. Buenos Aires, Argentina

2000

Pasillos, Sicardi Gallery. Houston, Texas, Estados Unidos

1999

Pasillos, ICI. Buenos Aires, Argentina

1995

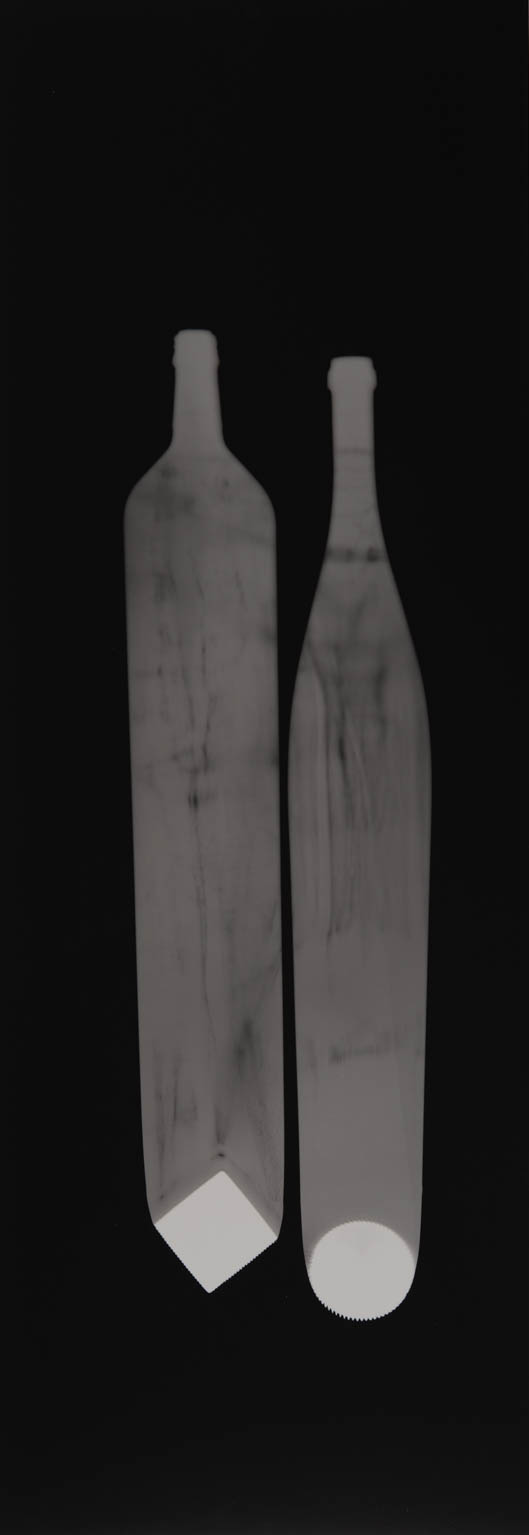

Fotos de nada, Fotogalería del Rojas, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires, Argentina

Group exhibitions

2021 – 2022

Reunión. Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2019

Formas de desmesura. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Curada por Verónica Tell

2017

Usos de la Fotografía VII / Fotos. Princeton University Art Museum, Filadelfia, Pensilvania, Estados Unidos.

Social Photography V. Carriage Trade, New York,Estados Unidos.

2014

Of Light and Time – Photos of others, Terrazzo Art Projects. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2013

Roberto Aizenberg: Trascendencia/Descendencia Colección de Arte Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat. Buenos Aires, Argentina

2010

50 Artists Photograph the Future– Cast, Higher Pictures Gallery. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

Escape from New York – Pasillos, Engine Room, Massey University. Wellington, Nueva Zelandia (2010) Project Space Spare Room, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia (2009) Curtin University of Technology, Perth (2008), Sidney Non-Objective, Sidney, Australia (2007)

2009

MA Curate MFA –Dials-Cielito lindo, Hunter College, Times Square Gallery. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

NewInSight – Dials, Art Chicago. Chicago, Estados Unidos

2008/9

Minus Space –Dials. MoMA PS1 Contemporary Art Center. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2003/8

Mapas abiertos: Fotografía Latinoamericana 1991-2002, Pasillos Museo de Bellas Artes. Bruselas, Bélgica (2008)

Amos Anderson Museum. Helsinki, Finlandia (2005)

Auditorio de Galicia. Santiago de Compostela, España (2005)

Sala de Exposiciones de la Ciudadela. Pamplona, España (2005)

Bienal FotoNoviembre, Centro de Fotografía Isla de Tenerife, España (2005) Fototeca de Nuevo León. Monterrey, México (2005)

Fundación Telefónica. Santiago de Chile, Chile (2005)

Centro de la imagen. Mexico DF, México (2004)

Museo Zapopán. Guadalajara, México (2004)

Palau de la Virreina. Barcelona, España (2003)

Fundación Telefónica. Madrid, España (2003)

2007

NewInSight – Cielito Lindo, Art Chicago. Chicago, Estados Unidos

2006

International Contemporary Art from the Harn Museum Collection Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, U. de Florida. Gainsville, Estados Unidos

Retratos de artistas, Galería Palatina. Buenos Aires

2005

From B.A. to L.A.: Mondongo, Tessi, Iuso, Prior, Grinblatt, Pasillos Track 16. Los Angeles, Estados Unidos

2003

Traces of Friday -Fotos de otros, ICA. Filadelfia, Estados Unidos

2002

The S-Files -Fotos de otros, El Museo del Barrio. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

Julio Grinblatt – Tricia McLaughlin – Ana Tiscornia, A. A. Wallace Gallery, SUNY, Old Westbury. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

Nuevas Tendencias -Fotos de otros, Museo de Arte Moderno. Buenos Aires, Argentina

Discoveries of the Meeting Place -Pasillos FotoFest. Houston, Texas, Estados Unidos

2001

Tipping Point -Fotos de otros, White Columns. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2000

Más allá del documento, Pasillos, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Madrid, España

Latin American Photographs. New View Points -Pasillos University of Texas at San Antonio Art Gallery. San Antonio, Estados Unidos

Awards

2012

Nominado para “Rema Hort Mann Foundation-Visual Arts Grant ” Fundación Rema Hort Mann. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2011

Nominado para “Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Award for Latin American Emerging Artists”, Fundación Cisneros Fontanals Art. Miami, Florida, Estados Unidos

Nominado para “Rema Hort Mann Foundation-Visual Arts Grant ” Fundación Rema Hort Mann. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2010

Tony Smith Award, Hunter College, CUNY, Nueva York, Estados Unidos

Nominado para “The Baum: An Emerging American Photographer Award”, The Baum Foundation y el SF Camerawork. San Francisco, Estados Unidos

Nominado para “Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Award for Latin American Emerging Artists”, Fundación Cisneros Fontanals Art. Miami, Florida, Estados Unidos

2007

Nominado para “Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Award for Latin American Emerging Artists”, Fundación Cisneros Fontanals Art. Miami, Florida, Estados Unidos

2006

Nominado para “Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Award for Latin American Emerging Artists”, Fundación Cisneros Fontanals Art. Miami, Florida, Estados Unidos

2004

Nominado para “The Baum: An Emerging American Photographer Award”, Glenn y April Bucksbaum, presentado por The UC Berkeley Art Museum y Pacific Film Archive. California, Estados Unidos

2002

Artist Recovery Fund, New York Foundation for the Arts. Nueva York, Estados Unidos

2001

Nominado para el “Bucksbaum Family Award for Emerging Photographers”, The Friends of Photography. San Francisco, California, Estados Unidos

Premio Banco Nación (Mención de Honor) –Fotos de otros. Buenos Aires, Argentina

1994

Premio Fundación Nuevo Mundo (Premio de Premiados) –Paisajes Paralelos, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. Buenos Aires, Argentina

1993

Premio Fundación Nuevo Mundo a la Nueva Fotografía Argentina -Retratos, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. Buenos Aires, Argentina

Collections

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston, Texas, Estados Unidos.

Museum für Fotografie, Berlin, Alemania.

Portland Art Museum. Portland, Oregon, Estados Unidos.

Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art. University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, Estados Unidos.

Light Work Collection. Syracuse, New York, Estados Unidos.

Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Museo de Arte Moderno. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Museo de Arte Moderno. Río de Janeiro, Brasil.

Colecciones privadas en Estados Unidos, España y Latinoamérica.